Article 5

Sunday Freeman, May 7, 1995

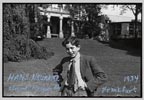

Bittersweet memories of schooldays in Frankfurt

John J. Neumaier

Out

of the blue came a letter from a thirteen-year old girl in Germany. Andrea

Nesswetter wanted to know how I remember my years at the Woehlerschule,

the public school I attended in my hometown of Frankfurt on Main. The

school was started in 1870, a year before the founding of the united German

Reich, and now it's about to celebrate its 125th anniversary. An exhibit

is planned, with photographs, memorabilia, and sketches of some of its

alumni.

Out

of the blue came a letter from a thirteen-year old girl in Germany. Andrea

Nesswetter wanted to know how I remember my years at the Woehlerschule,

the public school I attended in my hometown of Frankfurt on Main. The

school was started in 1870, a year before the founding of the united German

Reich, and now it's about to celebrate its 125th anniversary. An exhibit

is planned, with photographs, memorabilia, and sketches of some of its

alumni.

I'm sending Andrea the materials she's requested and as I wrote down the

memories of a German Jewish school boy I thought they might also be of

interest to readers of this column.

The Woehlerschule of my time offered four years of elementary education

and a 9-year secondary program in what is called a Gymnasium, which prepared

students for university. I was in the elementary school from 1927 until

1931 and the Gymnasium from 1931 to 1933. Adolf Hitler came to power during

that last year, having been named chancellor by President von Hindenburg

on January 30, 1933.

In my first school year I was hardly aware of any significant difference

between myself and the other 53 boys who

were in my class. Most of us took pride not only in being German, but

in being citizens of the once "Free City" of Frankfurt, though

it had lost that honorable status in 1866 when, on orders of Bismark,

it was incorporated into Prussia because it had been on the wrong side

in Prussia's war with Austria. Frankfurt was also the birthplace of Germany's

greatest poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Frankfurters' feeling about

their city is epitomized in the modest rhyme “Es will mir nicht

in den Kopf hinein, wie kann nur ein Mensch nicht von Frankfurt sein"

(literally, "It just can't enter my head, how can a person not be

from Frankfurt").

On one of my first days as a new pupil, a friend and his mother walked

with me to the Woehlerschule which was located some few blocks from my

home in Frankfurt's elegant Westend. That was the day the pupils were

separated into three different groups for the purpose of the state-sponsored

program of religious instruction. One group of my schoolmates turned out

to be Protestant (evangelisch), another was Catholic, and the smallest

group consisted of about eight or ten Jewish boys. For some reason I felt

elated to belong to so small a group, just a few children. Of course I

had been aware of my Jewish religious background but my family, like most

German Jews, was fully assimilated. (Slightly less than one percent of

Germany's population was Jewish. Synagogue prayer books included fervent

prayers for the well-being of the leaders of the fatherland; and before

1918 there were prayers for the Kaiser himself.)

I knew that my friend and his mother were Catholic though I attached no

special significance to the fact. Yet, when I walked home with them, and

saw my mother looking for me out of the window, I hollered with unmistakable

enthusiasm: “Mutti (mother), I'm Jewish, I'm Jewish." While

I have never denied my ethnic background, in the years to come I found

out that this was nothing to shout about in Nazi Germany. Looking back

on the incident I realize that this grouping of the pupils by their religion

reinforced feelings of separateness which were later to play into the

hands of the organized anti-Semitism that was so crucial to Nazi mythology

and ideology.

Another scene comes flooding back. How sad I was at the loss of my new

leather Schulranzen (backpack). It was a

treasured present from my parents. I went in tears to the teacher. It

turned out that it was still in the class room, but I

couldn't see it because it was on my back - a foreshadowing perhaps of

my eventual career as an absent-minded professor.

The elementary teacher was a very important figure for the school children,

since he or she remained with the same class for all their four years.

How affectionately I remember the revered man who was our teacher! Caring,

warmhearted, inspiring, Ernst Kaiser - our own Kaiser as we sometimes

referred to him - could make even German grammar interesting. He found

time to play Fussball (soccer) with us when school was out. He led us

through the forest trails of the Stadtwald on holidays, and sometimes

he took us picnicking in the Taunus, a beautiful mountain range nearby.

My mother was well known as a concert singer. A native of Vienna, she

had been first contralto at the renowned Frankfurt opera, where she sang,

among other roles, Carmen in "Carmen", Queen Amneris in "Aida",

Count Orlovsky in "Die Fledermaus", and Hansel in "Hansel

and Gretel". Sometimes people asked whether I had inherited her voice.

Once it became known that I had what sounded like the deep baritone of

an adult, I was led around to different classes and to the amusement,

I suppose, of the pupils their six-year old school chum would boom out

such songs as Lehar's "Yours is my heart alone". I need not

add how proud I was to be the son of Leonore Schwarz (mother's stage name).

After elementary school I was looking forward to entering Gymnasium and

to wearing the academic visor cap that

identified its proud students. But then Hitler came to power. It would

be difficult for German pupils of today, and indeed for Germans born after

the Nazi period, let alone Americans, to imagine what it was like to live

through that time, to encounter daily so many brown-shirted men (Nazi

stormtroopers) and uniformed members of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler youth),

greeting each other and everyone else with "Heil Hitler" instead

of "Good morning" or "Good day", and to see the Nazi

flag with the Swastika symbol wherever one went, or to be forced to hear

Hitler's speeches blasting out in public squares, even the Opernplatz.

At first I encountered no personal animosity from my fellow students.

But then they played a schoolyard game in which a dozen or so boys would

circle around a Jewish boy and kick him and call him names. It was then

that my parents transferred me to a small private co-educational school

for Jewish children.

In 1965, some thirty-five years after I had left his tutelage, I sought

out my old teacher Ernst Kaiser for what

turned out to be a moving and bittersweet reunion. I was spending the

summer, as Visiting Professor at the University of Frankfurt, the Goethe

Universitaet. Herr Kaiser was living in retirement in Darmstadt and he

and Mrs. Kaiser welcomed me warmly. I treasure to this day the present

he gave me, a booklet we pupils had made for him, full of personal photographs

and dedicatory remarks, many in rhyme. Both of us were touched as we leafed

through it, mindful of all that had taken place since those long ago days.

I was embarrassed when he insisted on showing me a document testifying

that, while he had served as a German officer during World War II, he

had persistently resisted the anti-Semitic campaigns of the Nazi years.

He was indeed a good man, whose main misfortune, like that of many others,

was that he was born to live through those terrible times. He was profoundly

shocked to learn how many of my family were killed by the Nazis.

My mother was among the millions of Jewish people murdered by the Nazis

for the absurd reason that they were born to Jewish parents rather than

to parents with a different religion. In 1988 I learned that her death

occurred in the Majdanek concentration camp, near Lublin in then German-occupied

Poland. In 1993 I visited the camp to honor her memory and to see for

myself. The horrible structures, the displays of victims' personal belongings,

the stark monument that shelters their ashes are wrenching reminders of

the unspeakable atrocities that were committed there.

Yes, it is not easy to look back on the tragic events of that period.

But it is necessary, so that German school children and children everywhere,

whatever their nationality, race, or religion, may learn the lessons of

that past, lessons that I hope will inspire them and all of us to work

for a future of mutual acceptance and respect for each other's humanity.